A Short History of Shorthand

01 Feb 2015From early recorded history, stenography, or shorthand has been used to translate oral information onto paper, which was later transcribed into a legible medium for publication. This process was often a painstaking one, requiring specialized knowledge to read and translate. In the process of transcribing spoken language, conventions took root and new words emerged, giving rise to literature. Today, many of the words we have at our disposal are products of stenography - yet despite its historical importance, stenography is a forgotten art.

Night Mooring at Maple Bridge – Zhang Ji, A.D. 730-780

The moon is setting, a crow caws in the frosty night air

Beneath the river maples, fishing lanterns flicker and sway

And beyond these city walls, from the temple on Cold Mountain

The midnight bell is tolling, for me in restless slumber.

One of the early reasons for stenography was limited resources - primarily time, although tortoises1 and teachers were not in steady supply. Early authors were “bandwidth limited”, forcing them to condense their vocabulary in order to efficiently refer to common phrases. Today we enjoy many of their typographical innovations, such as ampersands, acronyms, and more recently, hashtags. While these conventions may have once shared frugal origins, we are quite happy to maintain them out of familiarity - for our readers’ sake, but as we soon realized, increasingly for our own benefit as well.

It turns out – perhaps unsurprisingly – as we started using more abbreviations, they began to take up permanent quarters in our own vernacular. Whereas Laser2 and Radar3 may have been deliberate interventions, many acronyms are more benign, eg. ASAP, A.D., B&B, ETA, FAQ, IQ, Q&A, RSVP. Some more contemporary slang can be easily deciphered based on its context and frequency, eg. AFAIK, FWIW, IMHO, IIRC. You may recall a moment of brief happiness when recognizing a new shorthand and then using it to communicate with another human being. This is not abnormal.

\(\begin{align} \int_0^{10} 6x^4 dx &= \left.\frac{6}{5}x^5\right|_0^{10} \\ &=\frac{6}{5}(10)^5 \\ &=1.2\times10^5 \end{align}\)

With the advent of terabyte HDDs and modern CPUs, one might imagine the structure of text alone would become less important - if shorthand were simply a means of abbreviation, then we should have little need for it today. But all along, the goal was never really conservation of ink and parchment, but the conservation of ideas. Far too many good ideas have been lost in a sea of poor notation4. Notation allows us to quickly employ declarative and procedural memories with the same ease which they come to mind. By standardizing their usage, we are able to communicate more effectively.

\(\begin{align*} x \in V & \Rightarrow x \in \Lambda \\ M, N \in \Lambda & \Rightarrow (M N) \in \Lambda \\ M \in \Lambda,\, x \in V & \Rightarrow (\lambda x M) \in \Lambda \end{align*}\)

Notation can also change how we think. Alonzo Church’s λ-calculus is one example of notation that changed not only just nomenclature, but usage as well. In the 1930s, Church developed a notation for describing computable functions called a lambda expression. Today we think of λ-expressions as a kind of shorthand for defining anonymous functions. More importantly, λ-calculus treats functions and data as the same and provides an alternative model of computation through substitution. While equivalent to the procedural model, it can lead to vastly different (and often far simpler) solutions to the same problem.

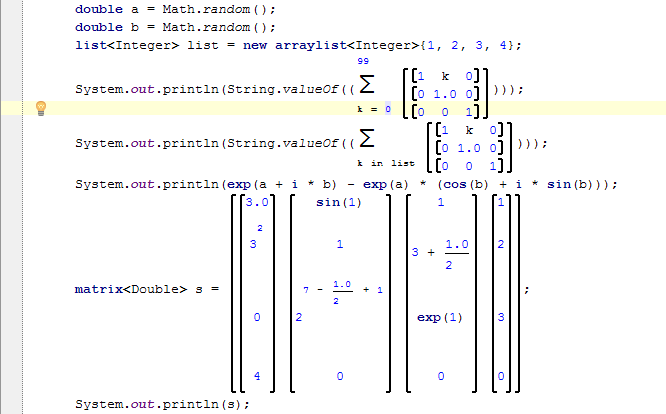

Translating a λ-expression in Java. Objects in editor are closure than they appear.

Today there are many writing systems which share a number of interesting similarities with traditional stenography. For example, Emmet is a shorthand for typing HTML. IntelliJ IDEA has a similar system of macros and keyboard shortcuts for automating repetitive programming tasks. Some television subtitles are now generated with a supervised speech recognizer5. And many handheld

Character amnesia is a growing problem in Asia.devices have predictive keyboards, which use Markov chains to suggest the next letter or word in a sentence. All of these are modern examples of stenography, yet they are radically different in form and function.

Character amnesia is a growing problem in Asia.devices have predictive keyboards, which use Markov chains to suggest the next letter or word in a sentence. All of these are modern examples of stenography, yet they are radically different in form and function.

This uncoupling between the creation and representation of text raises a number of intriguing questions. With the sudden ease of which we can create new abstractions and programming shorthands through macros, polymorphism and reflection, what is the appropriate level of notation required for a particular task? With the availability of code generation tools that write code, type systems for verification, and powerful IDEs to understand how it fits together, how do we differentiate between source and target? And who, or what, is the audience? These are not new questions6, but their significance today has only become more apparent.

Some editors like MPS treat text as an intermediate format, rather than the "source". This enables some degree of flexibility in the composition and presentation of code.

Let us consider a few examples. Conciseness is one desirable property in language design, although achieving it while maintaining precision is often quite challenging. Even in Java, one of the most carefully guarded7 programming languages today, new language features have created the potential for ambiguous code. Method references are a shorthand in Java 1.8 whose simplicity apparently outweighed the potential ambiguity.

public class Foo {

private interface F<T, R> {

R apply(T arg);

}

public String bar() {

return "foo";

}

public String bar(String foo) {

return foo;

}

public static String bar(Foo foo) {

return "bar";

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

F<String, String> f1 = new Foo()::bar;

System.out.println(f1.apply("OK")); //Prints "OK"

F<Foo, String> f2 = Foo::bar;

//Compile error: reference to bar is ambiguous

}

}Foo::bar refer the instance method bar() or the static bar(Foo foo)?

In Kotlin, there are no static members, making this somewhat less of an issue. However unlike Java, which is capable of distinguishing method references based on the type signature, Kotlin does not support ambiguous method references (ie. function references) to overloaded functions. It should be noted that while it is not possible to resolve ambiguous method references in Java without altering the syntax, disambiguating overloaded functions in Kotlin ought to be relatively straightforward.

fun foo() = "bar"

fun foo(bar : String) = bar

fun main(args : Array<String>) {

var f1: (String) -> String = {s -> foo(s)}

println(f2.invoke("OK")) //Prints "OK"

var f2: (String) -> String = ::foo

//Compile error: Overload resolution ambiguity

}::foo refer to the niladic or monadic foo? The λ parameter gives us a clue.

We can see how removing certain elements of notation may occasionally lead to ambiguity. Likewise, by adding notation we can also gain additional expressiveness and precision. For example, annotations in Java 1.58. Java has added a small number of language features and keywords since its inception, including assert and enum9. But perhaps one of the best examples of this can be found in a typesetting language called \(\TeX\).

\overbrace { (r_1 + r_2 + \cdots + r_w)^v = }^{\text {1}}

\underbrace{ \sum_{k_1 + k_2 + \cdots + k_w=v} }_{\text {2}}

\overbrace { v \choose k_1, k_2, \ldots, k_w }^{\text {3}}

\underbrace{ \prod_{1\le t\le w}r_{t}^{k_{t}} }_{\text {4}}\(\TeX\) was conceived in the late 1970s by Donald Knuth10, prior to the era of IDEs and modern text editors. It consists of a set of commands that exactly specify the visual arrangement of text on a page, and has been used for this purpose in academic circles for nearly four decades. Despite its popularity, \(\TeX\)has remained largely unchanged over that time, owing in part to a flexible system of macros11. Macros (short for macro instructions), are a substitution rule for replacing text, which in \(\TeX\)’s case, occurs during compilation.

\def\smz#1#2{ #1_1 + #1_2 + \cdots + #1_#2 }

\def\sqt#1#2{ #1_1, #1_2, \ldots, #1_#2 }

\def\pdx#1#2{ \prod_{ 1 \le #1\le\ #2 } }

\overbrace { ( \smz{r}{w} )^v = }^{\text {1}}

\underbrace{ \sum_{ \smz{k}{w}=v } }_{\text {2}}

\overbrace { v \choose \sqt{k}{w} }^{\text {3}}

\underbrace{ \pdx{t}{w} r_{t}^{ k_{t} } }_{\text {4}}In automatic programming, macros are not an uncommon feature - the C preprocessor performs lexical substitution prior to compilation. IDEs and text editors offer increasingly sophisticated keyboard macros under various names (eg. templates, macros, autocorrection). And many build tools incorporate document generators and string expansions that substitute and rewrite portions of source code. In a way, this gives programmers the ability to take notation into their own hands. It is unclear whether this is a good idea.

The key, it seems, to make automatic programming work is readability. In a perfect world, we might never have to write a single line of code twice. But perhaps what we should really be working towards, is not necessarily the conservation of keystrokes, but rather the conservation of ideas through effective notation. For all the time we spend writing code, albeit plenty, is dwarfed by the amount of time others spend trying to understand it (and failing to do so, spin off their own version with the same reckless abandon we poured into the first).

Did you know? Frank Liang spent five years12 studying a better hyphenation algorithm for \(\TeX\)13. Assuming Liang’s Algorithm has saved two minutes per year for each of a million readers (in academic journals, textbooks and CVs), Liang has singlehandedly saved over a century.

While the process of rapidly writing code is well-attended, the limiting factor in developer productivity is not the bandwidth of our fingertips on keys, but rather the attention span it takes to process their collective output. This is evident on a large scale in commercial code reviews, but also on an individual level, in the time it takes to effectively learn a new language or framework. It is not unreasonable to imagine how an upfront investment in readability could result in a hundredfold savings in time spread over a large userbase.

With this in mind, we should think of programming as an exercise in good notation. Notation matters - but not because it is easier for us to write. It is often convenient to choose a notation that our team is most familiar with, or with the most votes votes on HN. But if we succeed, we will not be the only ones maintaining it in ten years. So experiment. And when you have a good idea, spare no effort to make it plain.

Further Reading

- Ye, Katherine. (2016, July 22). Notes on notation and thought

Footnotes

-

Oracle bone script. (2015, January 17). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Oracle_bone_script. ↩

-

Gould, R. Gordon (1959). “The LASER, Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation”. In Franken, P.A. and Sands, R.H. (Eds.). The Ann Arbor Conference on Optical Pumping, the University of Michigan, 15 June through 18 June 1959. p. 128. ↩

-

Radar. (2015, January 30). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Radar. ↩

-

Although even average ones have stayed afloat with good notation. ↩

-

Imai, Toru. (2012). “Speech Recognition for Real-time Closed Captioning,” Broadcast Technology No. 48, pp.1-9. ↩

-

Wesch, M. (2007, January 31). Web 2.0. The machine is us/ing us [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLlGopyXT_g. ↩

-

Goetz, B. (2007, January 31). Stewardship: The sobering parts [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2y5Pv4yN0b0. ↩

-

Java annotation (History). (2015, January 20). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Java_annotation#History. ↩

-

Java language keywords. Oracle Corporation. https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/nutsandbolts/_keywords.html ↩

-

Author and computer scientist at Stanford University, more famously known for writing The Art of Computer Programming. ↩

-

Knuth, D. E. (1986). Definitions (also called Macros). The TeXbook. https://web.mit.edu/jgross/www/LaTeX/texbook.pdf. ↩

-

Liang, F. M. (2010). Interview. http://tug.org/interviews/liang.pdf. ↩

-

Liang, F. M. (1983). Word Hy-phen-a-tion by Com-put-er (Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University). https://www.tug.org/docs/liang/liang-thesis.pdf ↩